Ship Conversions at the Baltimore Yards

The SS Emma Maersk before (left) and during (right) a major conversion project performed by Bethlehem Steel shipyard workers in the early 1980s. Notice the new 157 foot mid-section splitting the letters of “Maersk Line”. BMI Archives, Bethlehem Steel Collection

Many Baltimoreans are familiar with the long legacy of our city’s shipbuilding industry, from Baltimore clipper ships of the nineteenth century to the massive output of liberty ships during WWII. Fewer people know about the difficult but vital work of ship conversions performed by Bethlehem Steel’s Baltimore shipyards in the second half of the twentieth century.

Ships are designed for a specific purpose, and building a new one requires a significant investment of time and money. When a vessel no longer meets the needs of its owner and operators, it can be cheaper to convert the ship from one design to another than to build a new vessel from scratch. Conversions were commonly done – and are still done today – to extend the lifespan of an aging ship, to outfit it with better navigational and loading equipment, and to increase cargo capacity. These projects were often as technically demanding as constructing new vessels, and the workers of Bethlehem Steel’s Baltimore shipyards were masters at ship conversions.

The vessels converted at Baltimore’s yards expanded the shipping capacity not just of the city but of the entire country. This significant but fleeting work is recorded in the documents and objects of the Baltimore Museum of Industry. We hope you enjoy this glimpse into our collections. Thank you for your support, which makes it possible to preserve and share stories like these.

The Baltimore Yards

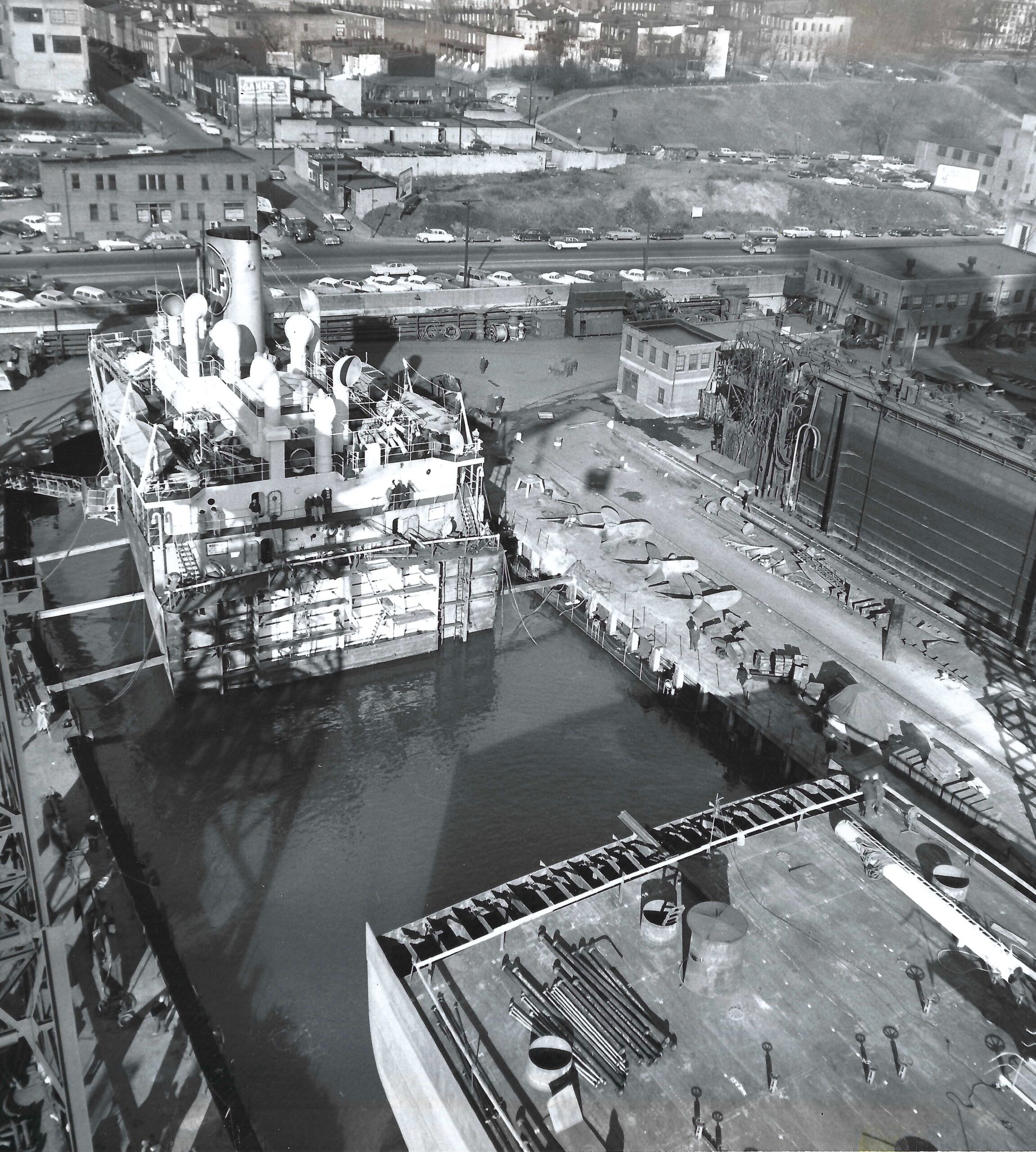

Aerial photo of the Bethlehem Key Highway Shipyard from 1968, BMI Archives, BGE Photo Collection

Bethlehem Steel’s “Baltimore yards” refers to two separate shipyards on the south side of the city: the Key Highway yard on the northeast side of Federal Hill near the Inner Harbor, and the Fort McHenry yard further east on the Locust Point peninsula. The Baltimore Museum of Industry now stands between the former locations of these two yards. Separate from the Baltimore yards, Bethlehem Steel owned and operated two other shipyards nearby. The oldest of Bethlehem’s yards was located at Sparrows Point, close to the company’s steel mill. The last of the four shipyards, which Bethlehem did not acquire until WWII, was located on the Fairfield peninsula on the south side of the Patapsco River.

At the outbreak of WWII, Bethlehem’s shipyards were called upon to increase their productivity and participate in the United States Maritime Commission’s Emergency Shipbuilding Program. While the yards at Sparrows Point and Fairfield concentrated on producing new ships, the Baltimore yards specialized in repairing damaged commercial and military vessels. After the war, the Fairfield yard ceased operations while the Sparrows Point yard and the two Baltimore yards continued to focus on ship building and ship repairs respectively.

It was not long before repair work at the Baltimore yards turned into ship conversions, significantly altering the design and capacity of aging ships to keep them competitive in a changing industry. Ships were becoming ever larger and more sophisticated with each passing year. Some of the growth in ship sizes can be attributed to the widespread adoption of standardized shipping containers in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Workers at the Baltimore yards soon developed a reputation for handling complex conversion projects. The yards altered both military and commercial vessels, sometimes converting a ship designed for one to a design suitable for the other. Some ships even underwent multiple conversions in their lifetimes. The Baltimore yards converted numerous vessel classes over the decades including deluxe cargo-passenger ships, container ships, molten sulfur vessels, and bulk chemical carriers.

Magazine advertisement describing Bethlehem Steel’s services at the Baltimore yards, BMI Archives, Port of Baltimore Bulletin – August 1970

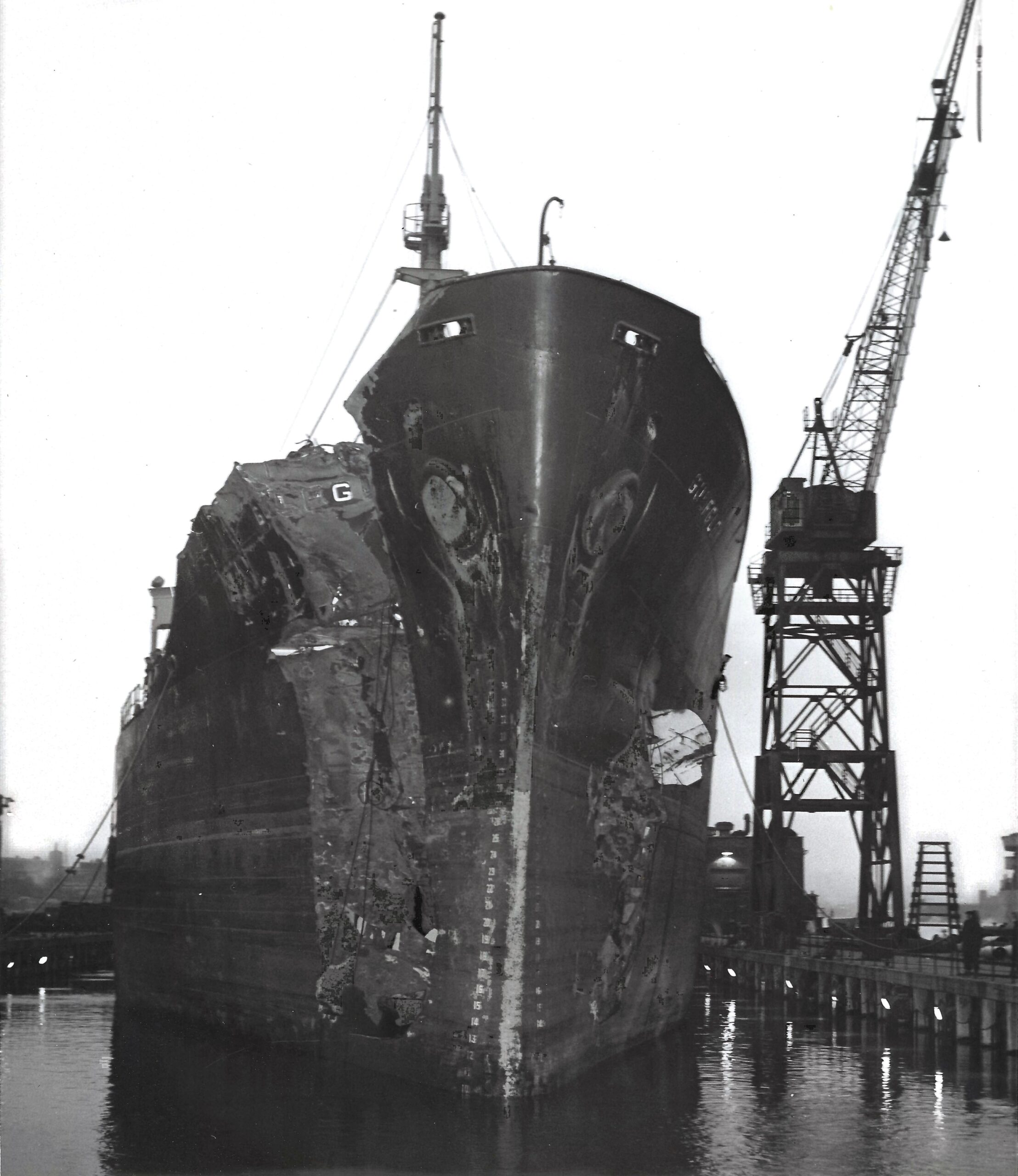

The Gulf Glow before and after extensive repair work at the Baltimore yards, BMI Archives, Bethlehem Steel Collection

On a foggy morning in March of 1952, the Gulf Glow and the Imperial Toronto, both oil tankers, collided in the Chesapeake Bay. The above photos show the Gulf Glow before and after its hull was repaired at the Baltimore yards. The repair work was completed in just 19 days.

The background of the “before” photo on the left shows a Whirley Crane identical to the one that now stands above the Baltimore Museum of Industry. The BMI’s crane was originally located at the Key Highway yard, and was floated to its current location in the 1990s after a brief stay across the harbor.

War Duty to Ore Duty

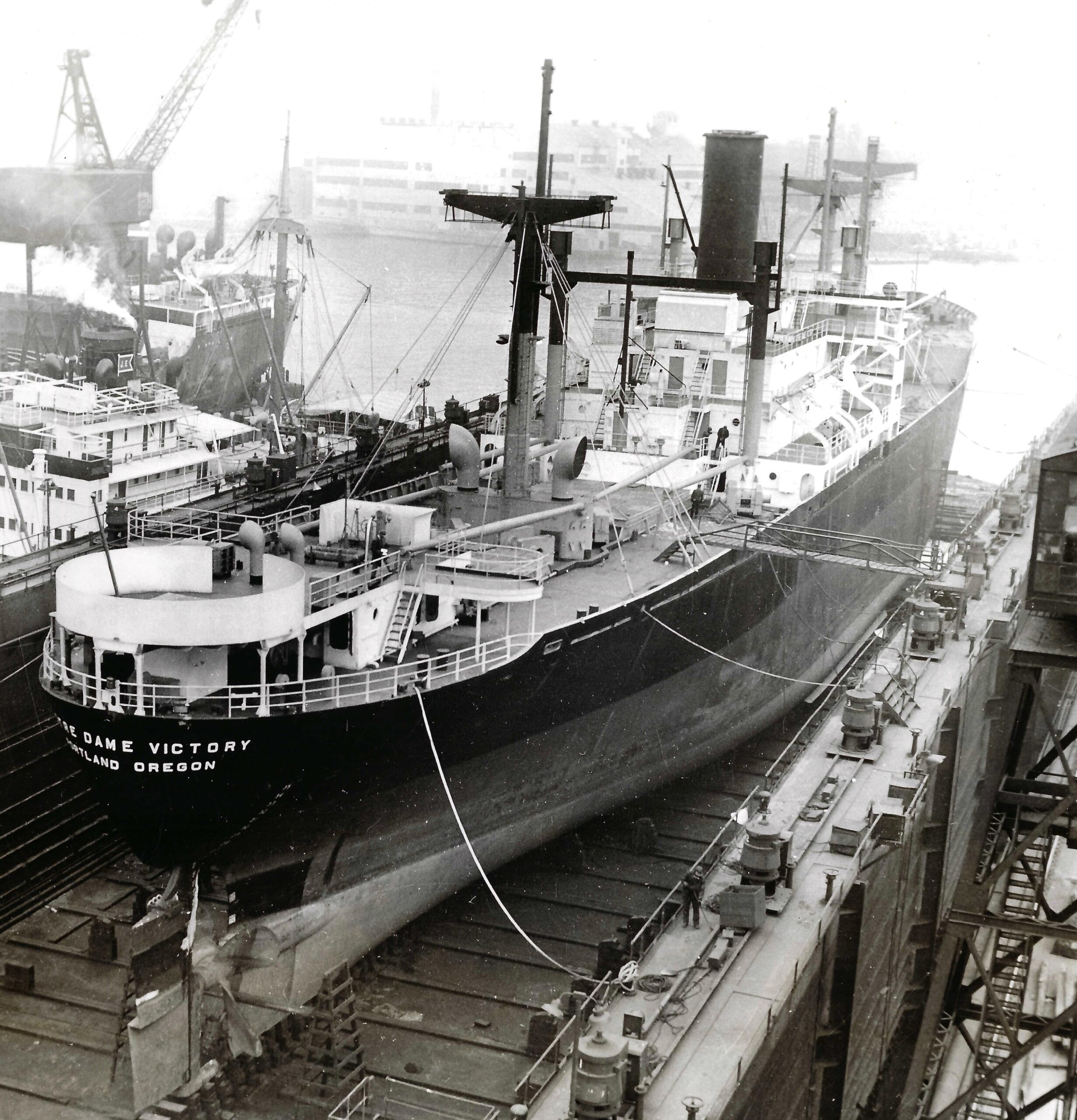

In the fall of 1950, the Cleveland-Cliffs Steamship Company faced a dilemma. They did not have enough vessels to handle the predicted quantity of iron ore that needed to be shipped from the Great Lakes in the upcoming season. The shipyards in the area were already at full capacity, and none of the ships being built were due to be delivered until the following year. That is how the Notre Dame Victory, originally a product of Portland, Oregon’s WWII shipbuilding industry, found its way to Baltimore for significant conversions.

The conversion of the Notre Dame Victory posed an unusual challenge for the Baltimore yards. Bethlehem’s workers needed to increase the cargo capacity of the vessel as much as possible while keeping the profile of the ship small enough to make the return voyage up the Mississippi River, through the Illinois Waterway, and on to Lake Michigan. A survey of the route from New Orleans to Chicago showed that the vessel would encounter 9 locks and 199 bridges or aerial passes during its 1500 mile return trip to the Great Lakes.

The new design of the vessel extended its length to 626 ft. and its beam to 70 feet. Its maximum height could not be larger than 53 feet 8 inches as it navigated the Mississippi River and waterways further north on its return trip to the Great Lakes. The final design of the vessel could be larger, but any part that exceeded the maximum height had to be test-fitted in Baltimore and then removed and stowed for transit to Chicago. Bethlehem’s workers built a new stack, mainmast, and three deck houses that could be partly or entirely removed during transit.

The Notre Dame Victory in drydock before work began, BMI Archives, Bethlehem Steel Collection

The Cliffs Victory near the end of its stay in Baltimore, BMI Archives, Bethlehem Steel Collection

Much of the vessel’s original cargo equipment had to be removed and reconstructed for its new purpose as an ore carrier. The most significant task was the insertion of a new 165-foot midsection fabricated at Sparrows Point and floated to the Baltimore yard. New bulkheads were built to divide the ship’s interior into ore holds, and sixteen ore hatches were added to the deck.

Just 3 months and 2 days after her arrival in Baltimore, the rechristened Cliffs Victory was ready to make its return journey to the Great Lakes. It left Baltimore on April 2, 1951, and arrived in New Orleans on April 18.

Even with the tallest components of the vessel stowed, 15 bridges that did not normally open for ship traffic on the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, the last leg of the Cliffs Victory’s return journey, needed to be cleared and temporarily opened. With this final challenge behind it, the ship arrived on Lake Michigan on May 9. During a brief stay at the South Chicago yard of the American Shipbuilding Company, Bethlehem Steel personnel supervised as the stowed houses, masts, and stack were lifted into place and the propeller and rudder were installed.

Cliffs Victory on the Chicago River, BMI Archives,

Bethlehem Steel Collection

The Cliffs Victory sailed from Chicago for the first time on June 4, 1951 to load ore at Marquette, Michigan for delivery in Cleveland. She served in the Great Lakes ore service until 1985. At some point in her career she was lengthened a second time to become the longest ship on the Great Lakes, and she was known for a time as the “Queen of the Lakes.”

Cliffs Victory on the Great Lakes,

BMI Archives, Bethlehem Steel Collection

Jumbosizing the Gulf Meadows

Answering the call for larger tankers to handle the world’s growing demand for crude oil, the Baltimore yards pioneered a concept referred to as “jumboizing” or “jumbosizing.” The process involved cutting out the midbody of a vessel and replacing it with a new, larger midsection. Many T2 oil tankers, a class of vessel built exclusively during WWII, were jumbosized in the late 1950s and 1960s to meet changing shipping standards.

The first T2 tanker to be jumbosized was the Gulf Meadows. The transformation of the tanker in 1957 increased the vessel’s petroleum capacity from 140,000 to 175,000 barrels and likely extended its service by more than a decade. The conversion took just 36 days, much shorter than the 18 months it would have taken to plan and build a new tanker of comparable size. The ship was renamed Gulf Beaver after the conversion.

The new midbody (foreground) of the Gulf Meadows being

aligned to merge with the original stern of the ship (background),

BMI Archives, Bethlehem Steel Collection

The Gulf Meadows deck house being transferred from the old midship (left) to the newly constructed midbody (right). The deck house was carefully transferred on tracks. The two ships had to be re-ballasted during the transfer as their combined center of gravity moved with the deck house. BMI Archives, Bethlehem Steel Collection

Commercial to Military Duty

The Maersk Estelle with midbody under construction (top), a welder working on the Maersk Estelle (bottom), and the PFC James Anderson Jr. during bay trials (right), BMI Archives, Bethlehem Steel Collection

Bethlehem Steel’s reputation and experience with ship conversions led to the Sparrows Point shipyard winning a $600 million contract in the early 1980s to convert three commercial cargo carriers into military vessels. The three roll-on/roll-off ships were previously owned by the logistics company Maersk. They were converted to military ships for the U.S. Navy’s Sealift Command Rapid Deployment Force.

Converting each ship involved inserting a 157-foot midbody and adding a new upper deck, a second deck house, and a helicopter platform. During the multi-year contract that began in 1982, the ships Maersk Estelle, Emma, and Evelyn were converted to the CPL Louis J. Hauge Jr., the PFC James Anderson Jr., and the PVT Harry Fisher respectively.

The finished vessels were selfsustaining, roll-on/roll-off container carriers. Each ship was equipped with a semi-self-slewing stern ramp, side port doors and ramps, and three tandem cargo cranes all designed for handling the equipment associated with a US Marine Amphibious Brigade.

To help secure the award of this contract, members of Local 33 of the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers of America agreed to a no-strike concession for the duration of the work. This concession kept 1,800 shipyard workers employed. The contract also benefited workers at the Sparrows Point steel plant, which rolled 19,200 tons of steel plate for the project.

Bethlehem Steel’s Legacy at the BMI

Much of the Bethlehem Steel material in the BMI collections was acquired during the multi-year Bethlehem Steel Legacy Project. Beginning in 2019, the museum worked to preserve objects and documents related to the Sparrows Point steel mill and build a community of Bethlehem Steel employees. Much of that work has concluded, but the project continues to shape the present and future of the BMI. The Legacy Project resulted in dozens of community-centered events, hundreds of documents and objects added to the BMI collection, and one permanent and two temporary exhibits.

One of the two temporary exhibits of the Legacy Project, Shuttered: Images from the Fall of Bethlehem Steel, has reached the end of its time at the BMI

this summer. Our collections team has spent the last few weeks removing and carefully storing the photos of J. M. Giordano which capture the experience of steel workers in the closing days of Sparrows Point. Shuttered is being removed to make way for a new temporary exhibit, The Daily Hustle: The Photographs of I. Henry Phillips, Sr. Phillips was a pioneering photographer for the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper who captured the lives and labor of Baltimore’s Black community from the 1940s to the 1990s. Like so many stories of twentieth-century Baltimore, Phillips’ career intersected with Bethlehem Steel. After serving in WWII and before joining the Afro-American, Phillips worked at Bethlehem’s Baltimore shipyards where he likely played a part in ship conversions.

The Baltimore Museum of Industry is grateful to the many community members who gave their objects, stories, time, and donations to help make the Bethlehem Steel Legacy Project a success. We hope you will join us to see The Daily Hustle when it opens this September, and to revisit the full story of Bethlehem Steel’s Sparrows Point mill with our permanent exhibit Fire & Shadow.

Former Bethlehem Steel employee Joe Lawrence and his family at the BMI’s Bethlehem Steel Legacy Garden. Photo by Mary Braman

The BMI is proud to be able to present stories like these from our extensive archives. You can support our efforts to preserve Baltimore’s industrial heritage with a donation to the museum today. Learn more at www.thebmi.org/donate, or contact Director of Development Jo Pressimone at (410) 727-4808 x129 / jpressimone@thebmi.org.